A key reason for women’s low labour force participation in developing countries is the burden of unpaid domestic work. Analysing data from rural Bangladesh, this article assesses whether electrification can make a difference by increasing access to time-saving technologies. It finds that women in electrified homes are able to divert some time away from housework to farm work and leisure, and have a greater say in decision-making.

This is the third post of a five-part series to mark International Women’s Day 2025.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2020), the global female labour force participation rate was 47%, compared to 74% for men. Women, particularly in developing countries, spend 3.2 times as many hours on unpaid domestic work as men (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2019). This unequal division of household responsibilities deepens systemic inequalities, hindering women's access to economic opportunities and perpetuating gender disparities. In addition, women often have limited decision-making power and access to assets and resources, preventing them from fully engaging in economic activities. Such disparities in labour market participation, coupled with the disproportionate burden of domestic work, create a cycle of restricted opportunities for women, limiting their social mobility and economic empowerment.

In developing countries, one of the main reasons for the burden of unpaid work on women is ‘energy poverty’, which limits access to time-saving technologies (Kohlin et al. 2012, Feenstra and Özerol 2021). Consequently, initiatives to alleviate energy poverty can also help narrow gender gaps in paid work and time allocation across various activities (Kohlin et al. 2012, Sedai et al. 2021). Access to electricity can be transformative – it can power homes and farms, and hence, reshape women's roles within the household, agriculture, and the broader economy. By addressing the intersection of energy access and gender equity, rural electrification holds the potential to reconfigure economic and social landscapes.

Institutional background: Electrification in rural Bangladesh

In our recent research (Gupta, Khan and Negi 2024), we focus on how rural electrification influences gendered time use, labour allocation, and decision-making, focusing on its implications for women's empowerment and economic participation. Bangladesh's ambitious Total Electrification Programme, spearheaded by the Bangladesh Rural Electrification Board (BREB), has led to an increase in household electrification rates from 40% in 2011 to 90% in 2019 (Ministry of Power, Government of Bangladesh, 2019). BREB's electrification programme has provided over 2 million electricity connections and increased the installed capacity to 22,482 megawatts (MW) by 2021-22.

Such rapid expansion has brought electricity to millions of rural households, creating opportunities to reduce the time burden of domestic work, improve productivity, and enhance gender equity. This progress aligns with global goals such as Sustainable Development Goal 5 (gender equality) and Sustainable Development Goal 7 (affordable and clean energy). While electrification's economic and developmental benefits are widely acknowledged, its impact on women's time use and participation in the labour market remains underexplored. Our study aims to bridge this gap, offering insights into how electricity access influences gendered labour dynamics and empowerment.

Shifts in work participation and time use

We use data from the Bangladesh Integrated Household Survey (BIHS), a panel survey data for rural households in the country. It provides detailed information on various aspects of rural households, including employment, asset ownership, agricultural production, and electrification status. The first two survey rounds were conducted in 2011-2012 and 2015, covering 6,500 households, while the third round was conducted in 2018-2019, covering 5,604 households. This rich dataset allows us to trace patterns over time, capturing the effects of electrification on household dynamics.

For our analysis, we assess households' access to grid electricity based on the availability of electricity connections in each household during each survey round. Our focus is on two primary sets of outcomes. The first set examines individuals' participation in non-agricultural wage labour, non-farm work, and cultivation activities.1 The second set explores time use, capturing the allocation of time to various activities such as farming, non-farm work, domestic work, and leisure activities like watching television.2 Since our interest is to analyse gender-specific shifts in activity participation and intra-household dynamics, we provide critical insights into how electrification impacts women and men differently.

Shifts in labour allocation and time use

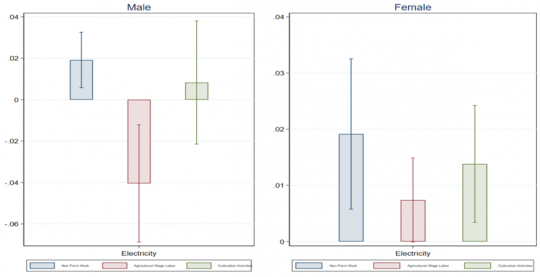

Electrification has brought significant changes to gendered labour patterns in rural households. For men, access to electricity is associated with a shift away from agricultural wage labour (a reduction of 4 percentage points) toward non-farm employment (increase of 1.9 percentage points). Women, on the other hand, are increasing their participation in cultivation activities (by 1.4 percentage points) (Figure 1). Our findings show that males diversify out of agriculture while females increase participation in agricultural activities, contributing to the trend of feminisation of agriculture in Bangladesh.

Figure 1. Electrification and activity participation

Note: The figure shows the regression estimates of household electrification for males (left panel) and females (right panel), where the outcomes are ‘dummy variables’ measuring the participation in non-farm work, agricultural wage labour, and cultivation activities separately.

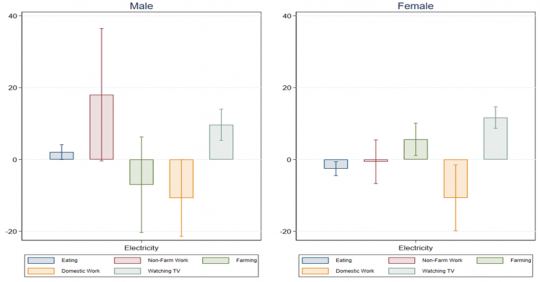

Figure 2. Electrification and time use

Note: The figure shows the regression estimates of household electrification for males (left panel) and females (right panel), where the outcomes are the number of minutes spent per day on different activities, namely – eating, non-farm work, farming, domestic work, and watching television.

Women in electrified households spend less time on unpaid domestic tasks (2.5% decline), such as cooking and caregiving, and reallocate this time to farming (16.7% increase). In contrast, for males, we observe increased time spent on non-farm work and reduced time allocated to domestic duties. For both women and men, we observe an increase of around 3.7-4.4% in time spent watching television (Figure 2).

Mechanisms

Our study identifies three key mechanisms through which electrification influences work participation and time use in rural Bangladeshi households:

Adoption of appliances: Electrified households report higher ownership of appliances like refrigerators, which reduce the domestic labour burden and free up time for work outside the home.

Improved agricultural practices: Electrification facilitates using electric pumps for irrigation, reducing reliance on manual labour and enhancing productivity in agriculture. Women's involvement in farming increases, particularly in tasks like planting and weeding, which align with the adoption of modern irrigation methods.

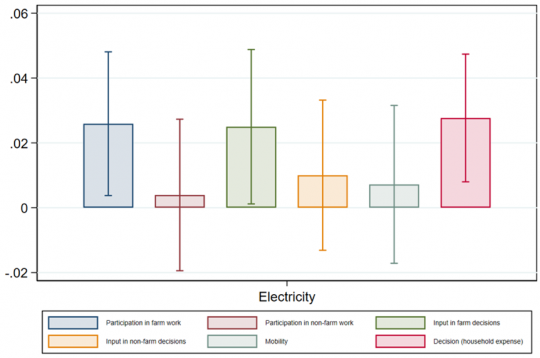

Enhanced decision-making: Devices such as mobile phones and televisions provide avenues for leisure and information access. This empowers women to play a more active role in household economic decisions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Electrification and women's empowerment

Note: The figure shows the regression estimates of household electrification on different outcomes for females (measured by ‘dummy variables’): their participation in farm and non-farm work separately, whether they make decisions related to farm and non-farm work, whether they can decide to go outside places including market, relatives, etc. (mobility), and whether they are a sole decision-maker in household expenses including food, clothing, education, and health.

Uneven impacts and persistent barriers

Despite its transformative potential, the benefits of electrification are unevenly distributed across women’s outcomes. We find no significant effect on women's mobility and participation in non-farm labour markets. Women's increased participation in farming without a corresponding improvement in mobility or participation in non-farm work reflects the complex interplay of norms and infrastructure development. While electrification may create opportunities for home-based economic activities, such as those related to agriculture, it may not be sufficient to dismantle the societal barriers that prevent women from entering the non-farm labour market.

Additionally, we find that the increment in men's time for non-farm activity and women's time for farming is significant only when electricity quality is good. This highlights the critical role of reliable electricity supply in ensuring the transformative potential of electrification.

Conclusion

Rural electrification can potentially be a transformative force for gender equity and economic development in Bangladesh. By reducing the time burden of unpaid domestic tasks, electrification enables women to engage more fully in productive and empowering activities. However, its full potential can only be realised through improved electricity reliability and complementary policies that address structural barriers and promote inclusivity.

As policymakers work towards expanding electrification initiatives, the lessons from rural Bangladesh underscore the need to integrate gender perspectives into infrastructure planning across the subcontinent. Electrification is not just about powering homes – it is about powering progress for women and their communities.

Notes:

- Non-agricultural wage labour includes occupations like construction labour, sweeper, factory workers, and transport workers, while non-farm work includes services, housemaids, NGO workers, and teachers. Cultivation activities include an individual working either as agricultural labour or working/farming on their own land.

- Non-farm work includes time spent in services, construction, and wage labour.

Further Reading

- Feenstra, Mariëlle and Gül Özerol (2021), “Energy justice as a search light for gender-energy nexus: Towards a conceptual framework”, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 138: 110668.

- Gupta, T, MT Khan and DS Negi (2024), ‘Agriculture, Electrification and Gendered Time Use in Rural Bangladesh’, Ashoka University Economics Discussion Paper 137.

- International Labour Organization (2020), ‘World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020’, ILO Flagship Report.

- Kohlin, G, E O’Donnell Sills, SK Pattanayak and CW Wilfong (2012), ‘Energy, gender and development: what are the linkages? where is the evidence?’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

- Ministry of Power (2019), ‘Glimpses of Bangladesh Power Sector’, Ministry of Power, Energy & Mineral Resources, Government of Bangladesh.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2019), ‘Enabling Women's Economic Empowerment: New Approaches to Unpaid Care Work in Developing Countries’, OECD Report.

- Sedai, Ashish Kumar, Rabindra Nepal and Tooraj Jamasb (2021), “Flickering lifelines: Electrification and household welfare in India”, Energy Economics, 94: 104975.

Tags: IWD2025 gender energy female labour force participation